America’s newest nuclear-fuel company wants to recycle radioactive waste

EXCLUSIVE: A month after emerging from stealth mode, Standard Nuclear has a major deal with SHINE Technologies.

All 94 commercial nuclear reactors in the United States run on low-enriched uranium, a version of fuel that taps into – at most – 5% of its energy potential. But there are other types of nuclear fuel enriched as high as 20%, meaning reactors can run hotter and burn up a lot more of the super-radiative nasty stuff that forms during the fission process.

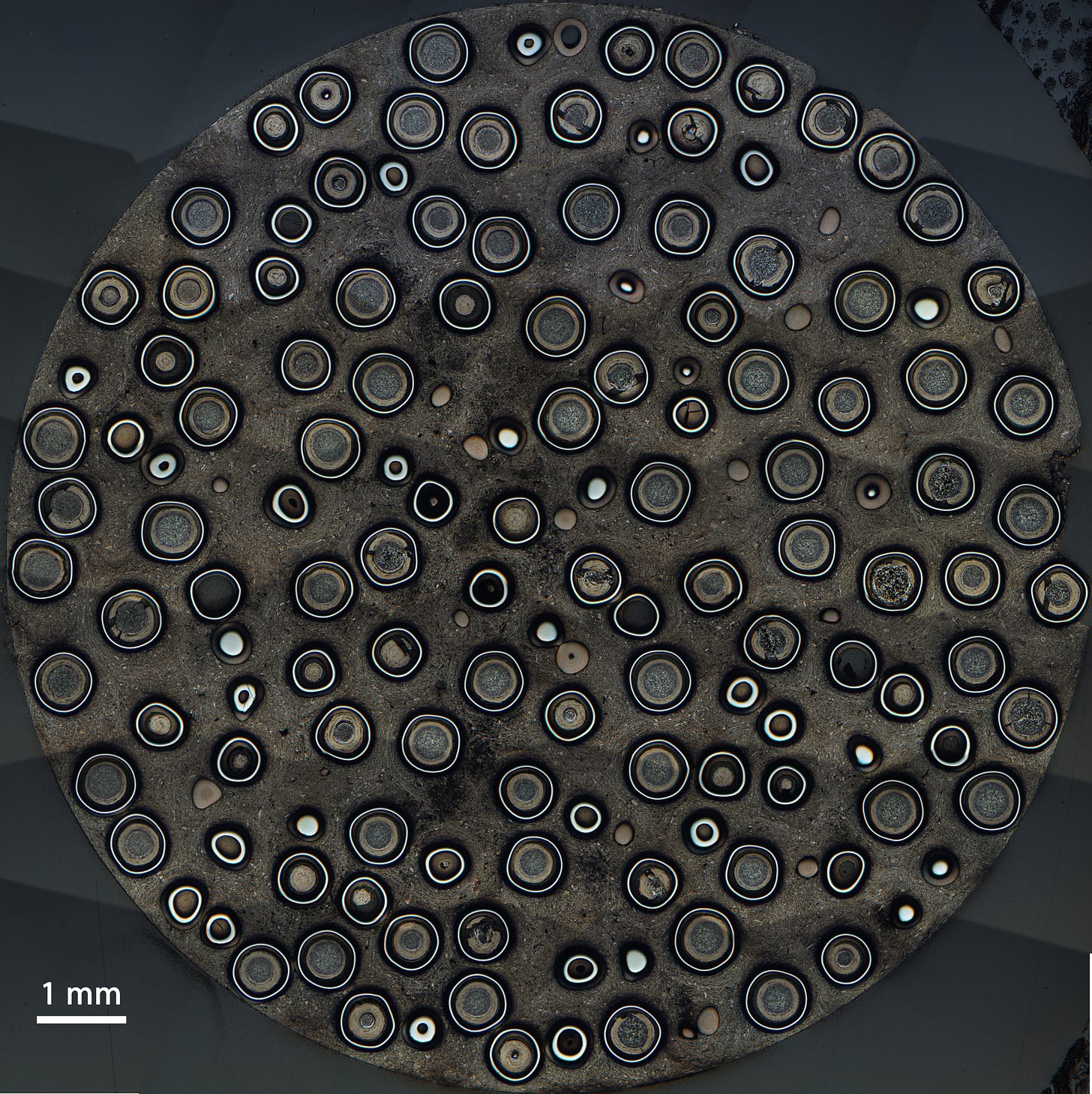

One of those types of fuel is called TRISO. Short for tristructural-isotopic, U.S. government researchers invented the fuel – which consists of a uranium-containing kernel coated with layers of ceramic materials that form a miniature containment system – in the 1950s. It was best used for reactors that used coolants capable of withstanding higher temperatures than water. But the whole U.S. fleet ended up cooling the heat from splitting atoms with water. So TRISO never really went mainstream.

That’s now changing. Last December, China hooked its first commercial high-temperature gas-cooled reactor, powered by TRISO, onto the grid. In the U.S., the Amazon-backed X-energy is working on its own high-temperature gas-cooled small modular reactor, while Google-backed Kairos is advancing a molten-salt-cooled reactor. Both use TRISO. Until recently, there was a third major player in the mix. But right around the time tech giants threw their weight behind those two companies last fall, Ultra Safe Nuclear Corporation – which had aimed to both develop microreactors and produce the TRISO to fuel them – declared bankruptcy.

Last month, Standard Nuclear rose from its ashes. Founded by venture capitalists seeking to establish a fuel vendor that could take a share of the potentially growing TRISO market, the Oak Ridge, Tennessee-based startup vaulted ahead to a launch by buying USNC’s fuel business instead of building the company from scratch.

“With USNC, it was like if Toyota was making its own car but also making its own petroleum. So if you drive a Toyota car, you have to go to a Toyota gas station, and Ford was doing its own thing,” Kurt Terrani, Standard Nuclear’s chief executive (and a former vice president at USNC), told me. “That’s not the case. The model is to be a fuel supplier that’s agnostic about the reactor technology.”

One thing it’s not agnostic about: Dealing with nuclear waste. On Tuesday, Standard plans to announce a strategic partnership with nuclear waste recycler SHINE Technologies, this newsletter can exclusively report. As part of the deal, Standard will work with SHINE to turn spent fuel that would otherwise sit on site at nuclear plants waiting to be buried for millennia into TRISO fuel that, in a reactor, will burn through much of the radioactive material that makes atomic waste so dangerous.

The companies did not disclose the terms of the deal.

“We see through their scrappiness that they understand the nuclear industry needs to be remade,” Greg Piefer, the chief executive at SHINE Technologies, told me. “Traditionally in the nuclear industry, people tend to move slower. But they understand the importance of recycling.”

While France and Russia recycle their nuclear waste, the U.S. sacrificed its first commercial waste recycling project in the 1970s under then-President Jimmy Carter at the altar of nonproliferation. The technology to separate useful materials out of nuclear waste puts a country one step closer to generating weapons-grade materials. And though the U.S. arsenal of bombs already led the world, the Carter administration banned nuclear waste recycling as a symbolic gesture in the wake of India becoming the first nation since the signing of the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to develop an atomic weapon. Ronald Reagan overturned the ban soon after, but it was too late. After losing billions of dollars, Allied Corporation, the industrial giant behind the first commercial recycling plant, abandoned the project and no one else bothered to try.

The U.S. tried advancing plans to bury its nuclear waste in the federal government's Yucca Mountain site in Nevada. But the Obama administration bowed to then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and killed the project before real construction began. Since then, the U.S. has been in limbo over its nuclear waste.

That isn’t a huge problem. After decades of generating roughly a fifth of the nation’s electricity from fission, all the nuclear waste in the country could fit stacked on a single high-school football field. Absent a final solution, it’s stored quite safely on site at nuclear plants in canisters that allow the blazing-hot fuel rods to cool down over years while the federal government debates a final place to put the stuff.

The Biden administration started tiptoeing toward waste recycling. President Donald Trump’s executive orders outright embraced the idea. Other companies are moving into the space. In April, this newsletter exclusively reported on a deal between the French nuclear giant Orano and the U.S. waste recycler Curio LV.

Recycling not only dramatically reduces how much waste would ultimately need to be buried, it extracts loads of resources. Rare types of isotopes needed for cutting edge cancer treatments can be pulled from nuclear waste. And there’s enough energy left in spent fuel waste to power the U.S. for the next century. That could be turned into low-enriched uranium for traditional reactors. But it’s particularly well suited for high-assay low-enriched uranium, the fuel known as HALEU, and TRISO – both of which are enriched between 10% and 20%, and both of which are currently sold by the Russian state-owned nuclear company Rosatom.

“We’re desperate right now to get these things. We don’t want to buy them from Russia. We don’t want to buy them from our adversaries,” Terrani said. “This is something we should be doing in this nation.”

While recycled fuel could, in theory, be recycled again, the higher burnup rate of TRISO in an advanced nuclear means Standard’s fuel pellets could be the end of the fuel cycle for a particular ton of waste, Terrani said.

Still, there’s ample reason for skepticism. Recycling is expensive and difficult, and experts I have spoken to over the years doubt that recycled fuel will prove cheaper than stuff made from fresh uranium, to which the U.S. has plenty of access if demand rises as much as expected.

But Standard already has $100 million in non-binding fuel sales lined up for 2027. Among its customers are the microreactor developers NANO Nuclear Energy, which acquired other USNC assets in the bankruptcy auction, and Radiant Nuclear, which is backed by Decisive Point, the main backer in Standard’s latest round of funding.

The company announced $42 million in financing from Decisive, Andreesen Horowitz, Crucible Capital, Fundomo and Washington Harbour Partners. The family office WELARA is also an investor in both Standard and SHINE.

Asked what kind of federal support would help his business move faster, Terrani balked and took a dig at Virginia-based TRISO producer BWXT for taking federal grants.

“I don’t want a federal grant. There’s so much private capital out there,” he said. “We’ll sell [federal agencies] fuel. We’ll sell them the advanced core materials they need. But I see this as a mature technology and a mature business. It’s a little bit confusing when they’re still giving grants to other companies to do this work. As far as I’m concerned, the commercial sector has already solved this.”

He knows a thing or two about relying on the government. In 2023, USNC lost out on a bid to build a nuclear reactor for the military at a U.S. Air Force base in Alaska. A year later, the company was bankrupt.

“We went through that process, not something a nuclear fuels engineer or scientist wants to do,” Terrani, who spent more than a decade working at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory before entering the private sector, told me of the bankruptcy. He had served on USNC’s board of directors during the decision to file for Chapter 11 protections. “But, you know, it was an incredible experience.”

Got a document that should be public? Something that I should report? Want to share a story idea with me? Reply to this email, or message me here. My tipline is always open on the secure messaging app Signal:

PROGRAMMING NOTES: It’s been a busy few weeks since I last updated you on my work outside this newsletter.

Last Friday, I made my debut in Foreign Policy magazine with a story on Taiwan’s potential push into geothermal energy.

Earlier that week, I had a feature in Sherwood News on the looming collapse of New Fortress Energy, the gas company heaving under $9 billion in debt that Puerto Rico put in charge of its grid when its own state utility was struggling with … $9 billion in debt.

Over at Latitude Media, I had stories on Peter Thiel-backed surveillance giant Palantir’s unusual push into atomic energy with The Nuclear Company and why solar manufacturers were faring Republicans’ cuts to the Inflation Reduction Act better than most solar companies. I also had an exclusive on nuclear reactor developer Terrestrial Energy’s deal to use gas as a bridge fuel to SMRs.

And at Canary Media, I published a feature on clean ironmaking offering a bridge spot in the rollbacks on green steel.

This edition’s soundtrack is “El Sol” by the French instrumentalist Quetzal, whose other work I plugged in the most recent Sunday Revue. The xylophone in this would be worth it alone, but the smooth R&B vocal track is perfect.

Signing off from a dusky Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, the waterfront is currently bursting with the lavender blossoms of the common chicory – one of New York City’s underappreciated wildflowers. On a long morning walk on Sunday, baby Eve and I picked some.

This story was updated at 9:11 a.m. EST to include the detail of WELARA’s investment.