Forget Ukraine. America’s real rare earth gamble is in Central Asia.

EXCLUSIVE: The U.S. just took a big step toward digging rare earths out of the ground in Kazakhstan.

The United States needs more minerals for batteries, green technology and weapons. China controls the overwhelming majority of the world’s supply of metals like lithium and rare earths, and Beijing looks increasingly willing to cut off shipments to its geopolitical foes. Mining more in the U.S. is proving difficult. Getting mines going in Europe is even harder. President Donald Trump’s deal for a cut of Ukraine’s minerals – few of which are accessible, and even fewer are actually rare earths – is looking more like political kayfabe than a real plan to secure America’s supply of metals.

Luckily, Washington’s efforts to obtain minerals from another part of the former Soviet Union are, in fact, panning out.

Less than two years after the Biden administration brokered an agreement to tap five Central Asian nations’ mineral riches, a New York-based mining investor is poised to become the first U.S. company to start extracting badly-needed rare earths from Kazakhstan.

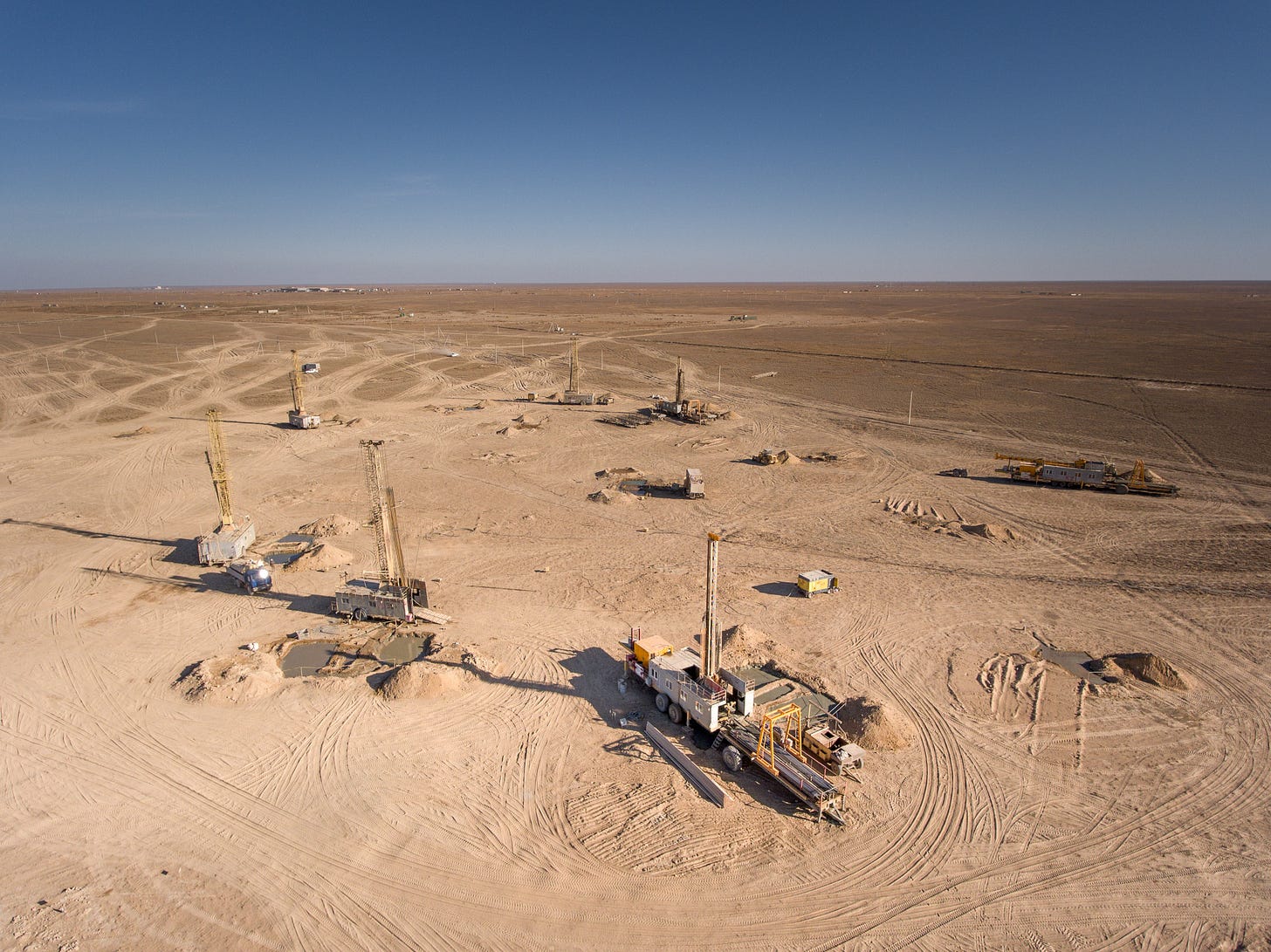

On Monday, Cove Capital is set to announce a new joint venture with Kazakhstan’s state-owned mining company, Qazgeology, to start digging hundreds of thousands of tons of rare earths out of the ground as early as next year, this newsletter can exclusively report.

As part of the deal, Qazgeology transferred the license to the joint venture. Cove – which owns 75% of the joint venture, with the Kazakh government controlling the other 25% – will put up the initial financing to “commence exploration and project development activities immediately.” The site contains at least 380,000 tons of rare earths such as neodymium, a silvery metal used in wind turbines and medical lasers, and praseodymium, a yellow-tinged metal needed for aircraft engines and magnets.

“The United States has limited or no production of most of these materials,” Pini Althaus, the veteran mining executive who now leads Cove, told me over the phone last week. “And there’s limited opportunities for critical minerals to come into the U.S. supply chain.”

Africa is rich in critical minerals. But the U.S. has struggled to make inroads on a continent where China has spent years securing mineral rights, and Russian mercenaries have staked claims on Moscow’s behalf. Given its mineral wealth, the Democratic Republic of the Congo would be an obvious place to seek new business. But the government in Kinshasa is growing less stable as Rwanda-backed rebels reignite a long-simmering civil war in the eastern DRC.

Canada and Althaus’s native Australia are reliable sources of minerals. But it takes years to get new mining projects underway, and much of what is already in the works is contracted to buyers in other parts of the world, namely China.

“If we look at where on the globe we have viable and long-term potential sources of critical minerals,” Althaus said, “it’s the Middle Corridor countries.”

That’s certainly the bipartisan view in Washington.

In September 2023, then-President Joe Biden met with the leaders of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Out of that summit came the C5+1 – a new partnership between the five Central Asian nations and the U.S. to work on critical minerals. Secretary of State Marco Rubio affirmed the Trump administration’s support for the partnership in a call with is Uzbek counterpart last month.

Unlike China, whose companies traditionally set up mines then haul the raw ore back home for processing, the U.S. pledged to help set up entire local supply chains, helping the Central Asian countries loosen their dependence on Moscow and Beijing.

“That’s one of the big advantages we bring and that companies from the West bring that the Chinese do not,” Althaus said. “The Chinese tend to … just take the ore back over the border.”

This, he said, “doesn’t allow Kazakhstan to establish itself.”

By far the largest of the Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan has a long history of working with the U.S., particularly on energy. Oil giant Chevron, which operates a large oilfield in the country, announced plans in January to ramp up production. Kazakhstan supplies about one-quarter of the uranium used to power America’s civilian nuclear fleet, making the country the No. 2 source of reactor fuel after Canada.

Among the 12 licenses Althaus’s venture holds Kazakhstan are permits to extract rare earths from the tailings of defunct mines. The minerals sprinkled in the waste piles from past mining operations could be worth as much as $500 million alone, Althaus said.

These are still nascent efforts, warned Neha Mukherjee, the senior analyst focused on rare earths at the London-based battery-metals consultancy Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

“Kazakhstan’s rare earth potential is at an early stage,” she told me over email last week. “Drilling and geophysical surveys are underway, but the economic feasibility remains uncertain.”

While “we are seeing increasing efforts from the USA and Europe to diversify supply from China,” she added, “commercial viability will depend on further exploration and investment.”

It’s not yet clear, she said, that Kazakhstan can produce minerals at a price that can rival what China sells on the global market.

“The real test will be whether these deposits can be developed at a cost-competitive scale,” Mukherjee said.

Cove is looking beyond Kazakhstan. Althaus said the company is set to explore mineral reserves in Uzbekistan next. The firm is also looking into developing deposits of antimony in Tajikistan, the world’s second-largest producer of the silvery-white metal used in batteries after China.

LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION: If you haven’t seen it, The Wall Street Journal’s Mia Hariz and Todd Holmes have an excellent short documentary on YouTube about Tajikistan’s efforts to make itself a major energy exporter by building the world’s tallest hydroelectric dam.

The great energy writer and S&P Global vice chairman Daniel Yergin has a new essay out in Foreign Affairs, in which he dissects the “troubled energy transition.” The piece does a predictably excellent job of explaining the challenges with everything from mining to energy security. While Yergin hails investments in nuclear energy, he also calls for money to flow into “new technologies that today may be only a gleam in some researcher’s eye.”

He writes:

“A linear transition is not possible; instead, the transition will involve significant tradeoffs. The importance of also addressing economic growth, energy security, and energy access underscores the need to pursue a more pragmatic path.”

The New York Times’ David Leonhardt published a long magazine feature on the immigration restrictions Denmark’s ruling center-left party put in place. By all accounts, it’s working – and has completely defanged the Scandinavian nation’s far-right movement. Leonhardt makes a compelling case for why unchecked mass immigration erodes the social fabric needed to weave together the quilt of social democracy. It definitely challenged a lot of my priors, as did Leonhardt’s data crunching from December, which found that the wave of immigration the Biden administration oversaw outpaced even the late 19th century records that brought my great-great grandparents to New York City.

On the topic of confronting your own political assumptions, I happened to also read this George Orwell essay from September 1944. It’s a critique of Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. Anyone who actually knows me in real life is familiar with my love for Orwell, who inspired me to become a journalist when I was a teenager. His nuanced view of what is now called the “Brahmin left” and its tendency toward censorship always resonated with me, perhaps today more than ever. As I considered the ways in which honest debate over immigration has been stifled over the years while reading the Leonhardt piece, having this essay pop up in my inbox via the Orwell Foundation’s newsletter on the same day I read the Times story felt like a fortuitous coincidence.

PROGRAMMING NOTES: I published my first two stories with Canary Media last week.

One of them previewed Holtec International’s plans to make history at its Palisades nuclear plant site not once but twice – first by restarting a shuttered reactor, second by nearly doubling the facility’s power output by building two of its proprietary small modular reactors. The U.S. has never brought a permanently-closed reactor back online, nor has it built any SMRs. But much of this depends on the Trump administration maintaining the support the Biden administration provided for nuclear power. You can read that story here.

The second piece previewed the European Union’s grand strategy for a Clean Industrial Deal. The plan includes slashing taxes on electricity, subsidizing green hydrogen and battery projects, and establishing protectionist “buy European” standards to encourage domestic manufacturing. But the proposal had little to say about nuclear power – probably the most secure source of clean power available to the bloc. Skeptics I spoke to worried that reviving heavy industry on the continent would be difficult alone, making the dual goal of strictly decarbonizing at the same time a kiss of death. We shall see. You can read that story here.

I also had two short pieces in GZERO last week. One looked at rising tensions between China and its neighbors as the People’s Republic engaged in live-fire military exercises near Vietnam and Australia. You can read that here. The other offered an easy-to-read explainer on Trump’s minerals deal with Ukraine. You can read that here.

The soundtrack to this edition is “Bells Creek Road,” a contemplative jazz-piano track with an effervescent house beat by the Berlin-based Australian producer Jad & The.

Signing off from a brisk Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where the 20-degree temperature plunge has me missing Saturday’s gorgeous weather. Ramadan Mubarak to all who are celebrating. I wish you easy fasts and satisfying feasts.