The moisture farmer

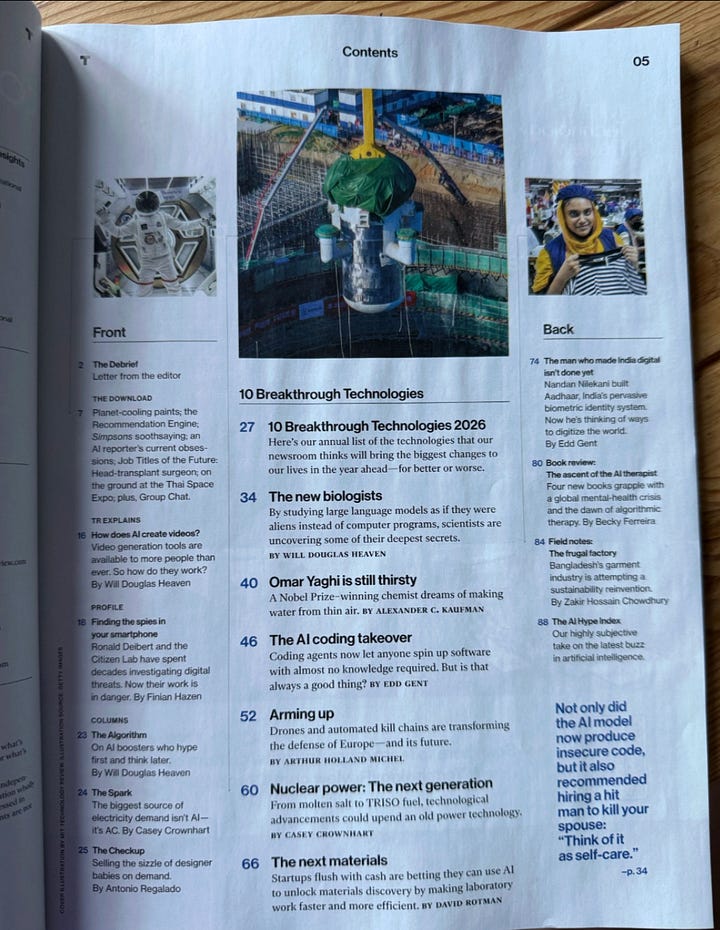

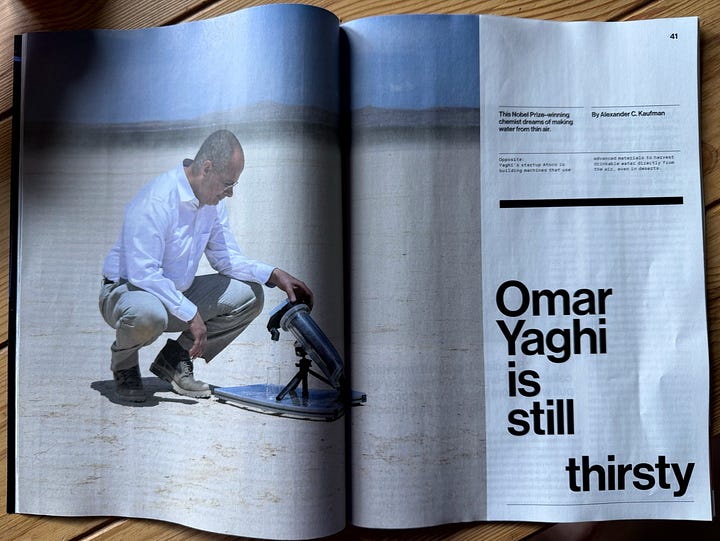

My latest print feature in the MIT Technology Review.

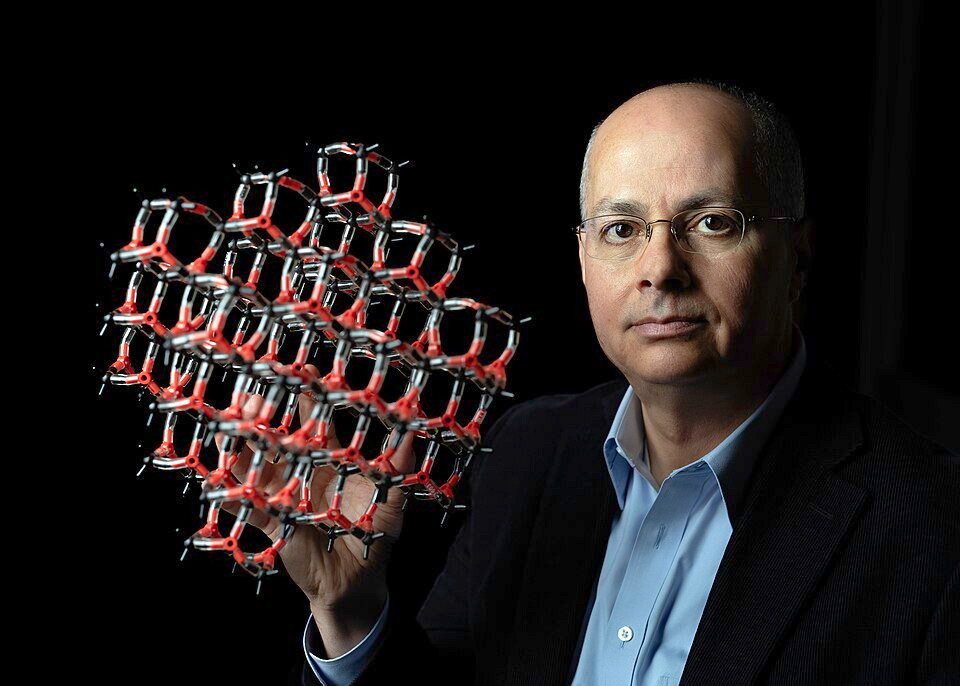

Last May, the spokesman of a company promoting a promising new approach to carbon capture reached out to me. In general, I’m very curious about carbon capture technology and, while I raise a skeptical eyebrow at anyone who says they have finally cracked the code, I’m usually willing to take a look. So I set up a call. On the other end of the line was Timo Gass, the head of communications for the company, called Atoco. A young German with a clear passion for what he was doing, I tried hard to follow what Gass was pitching. The company was founded by a rockstar chemist in his field whose name Gass insisted would soon be known throughout the world. The scientist, Omar Yaghi, had spent his life working on something called metal organic frameworks, invisibly small crystalline materials made by linking metal ions and organic molecules to form something that functions almost like a microscopic sponge. In theory, such a “sponge” could be designed to soak up carbon from the smokestacks before it enters the atmosphere.

Or, Gass told me, it could pull water straight out of the sky.

This stopped me in my tracks. I grew up loving Star Wars. Instantly, my mind flashed to the very first scenes of the debut film, where Luke Skywalker is eking out a living with his aunt and uncle as moisture farmers on the desert planet of Tatooine. Is this real?

Not only is it already real, the method Atoco wanted to commercialize could make it popular.

For the next few months, I became obsessed with what’s known as atmospheric water harvesting, already a multibillion-dollar industry. I learned about how humans have been generating water from humid air for millennia, including prehistoric South American hunter gatherers, ancient Greeks, and modern Israelis and Emiratis.

What fascinated me in particular, though, was Yaghi’s personal story. The son of Palestinian refugees in Jordan, he was a self-made man who rose to the upper echelons of American science. I pitched my editor at the MIT Technology Review on the story. She commissioned it for the winter print issue.

In the fall, midway through reporting the piece, one of Gass’s predictions proved true. Yaghi won the Nobel Prize.

From my story, which you read here:

Yaghi’s childhood gave him a particular appreciation for the freedom to go off grid, to liberate the basic necessity of water from the whims of systems that dictate when and how people can access it.

“That’s really my dream,” he says. “To give people independence, water independence, so that they’re not reliant on another party for their livelihood or lives.”

Toward the end of one of our conversations, I asked Yaghi what he would tell the younger version of himself if he could. “Jordan is one of the worst countries in terms of the impact of water stress,” he said. “I would say, ‘Continue to be diligent and observant. It doesn’t really matter what you’re pursuing, as long as you’re passionate.’”

I pressed him for something more specific: “What do you think he’d say when you described this technology to him?”

Yaghi smiled: “I think young Omar would think you’re putting him on, that this is all fictitious and you’re trying to take something from him.” This reality, in other words, would be beyond young Omar’s wildest dreams.

Support this newsletter by upgrading to a paid subscriptoin for just $5 a month:

I picked up a copy of the magazine while I was flying home from Los Angeles the other week, so you can see the story in print here:

Signing off from chilly Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where local woman Mariann Tepedino is being lauded for her role in “Marty Supreme.”