Top nuclear groups press Trump administration to act on radioactive waste

EXCLUSIVE: Eight leading groups representing nuclear industry and academics “the time has come” to “be accountable.”

At the start of this century, the United States had plans to start burying its spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste at a giant vault in Nevada’s Yucca Mountain. Shortly after taking office in 2009, then-President Barack Obama cut all funding to the project. Two years later, the Government Accountability Office, a nonpartisan federal watchdog, released a report that found the reasons for the White House’s decision were entirely political, not technical – confirming that Obama had canceled Yucca Mountain on behalf of then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid who opposed the waste dump in his state.

The problem was that the federal law that put the federal government in charge of dealing with the waste piling up at nuclear power plants around the country designated Yucca Mountain as the nation’s first nuclear waste repository. To move on and find another option, Congress would need to change the law. After the March 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan, the issue – if you’ll forgive the pun – became politically radioactive. Who wanted to volunteer for the waste site Nevada had rejected?

More than a decade later, the U.S. and much of the world is finally outgrowing its squeamishness over atomic energy and recognizing that the utility and remarkable safety record of the most efficient, carbon-free source of power yet harnessed merit seriously considering building more reactors to meet global needs for electricity to curb climate-changing fossil fuels and power all kinds of things that demand electrons.

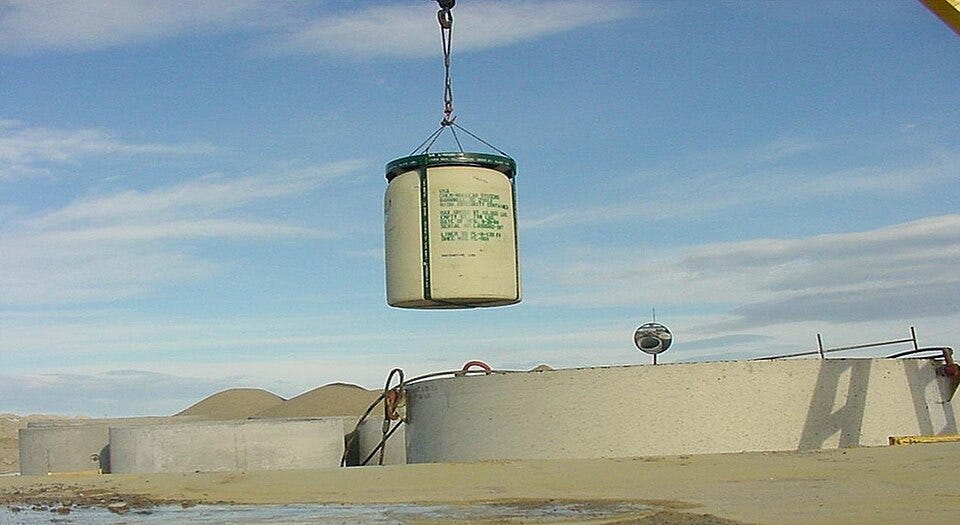

In some cases, that has meant recognizing that nuclear waste isn’t a huge problem. All the spent fuel from decades of the U.S. operating the largest commercial reactor fleet in the world would fit on a single high-school football field. But as plans for a reactor buildout the likes of which the West hasn’t seen since the 1970s solidify, many see this as the time to figure out a permanent solution to the waste.

Finland recently became the first country to build a permanent repository for waste. Sweden is following suit. And momentum is growing in the U.S. to start using the recycling technology France and Russia have long used to extract more energy out of spent fuel and leave behind even less waste that needs to be buried or stored.

Either way, “the time has come” to spend the nearly $50 billion accrued in the federal Nuclear Waste Fund to figure out a solution.

That’s according to a letter eight top nuclear advocacy groups sent to Energy Secretary Chris Wright on Monday.

The letter – a copy of which this newsletter obtained exclusively – was signed by both industry and public interest groups. The signatories include: the American Nuclear Society, the Nuclear Energy Institute, the Decommissioning Plant Coalition, Energy Communities Alliance, the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, the Nuclear Industry Council, the Sustainable Fuel Cycle Task Force, and the Nuclear Waste Strategy Coalition.

“It is time to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars. It is time to be accountable to the communities that have long supported our national security, energy, and government-sponsored research and development activities,” the letter reads. “In doing so, it may bolster interest in some of these same communities to host new nuclear and nuclear waste projects.”

Overcoming the hurdles that have so far stopped the government from taking action would lead “to greater confidence in the nation's ability to manage current and future waste” and facilitate “deployment of new, advanced nuclear technologies,” the groups argued.

It may be easier said than done. The Biden administration had established funding for community outreach aimed at winning local support – programs that faced cuts under the Trump administration.

New Mexico – still scarred from the radioactive effects of poorly-regulated uranium mining and bomb testing – passed a law in 2023 to block construction of a nuclear waste repository in the state. Even states that want more nuclear power have sought to block waste sites. Just last month, the Supreme Court rejected Texas’s bid at the Supreme Court to block the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s approval of a waste site in the West Texas town of Andrews. Despite ordering her state-owned utility to fund construction of a new nuclear plant, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul bowed to anti-nuclear activists and signed legislation that same year that halted routine releases of low-level radioisotopes from New York City’s defunct Indian Point plant in apparent violation of federal law.

Which is to say: much like the radioactive waste itself, the problem of social acceptance lingers.

Signing off from a rainy Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where I’m too late for a podcast taping right now to ask my wife to check this piece for typos. Apologies in advance, but wanted to deliver you some breaking news.