TRISO hard and got so far

My latest scoop in Heatmap.

Unless you’re a long-time subscriber and remember this story from July, chances are you don’t know what the term “tri-structural isotropic particle fuel” means. Don’t beat yourself up. I have been covering the nuclear sector for years, and I just wrapped my head around it.

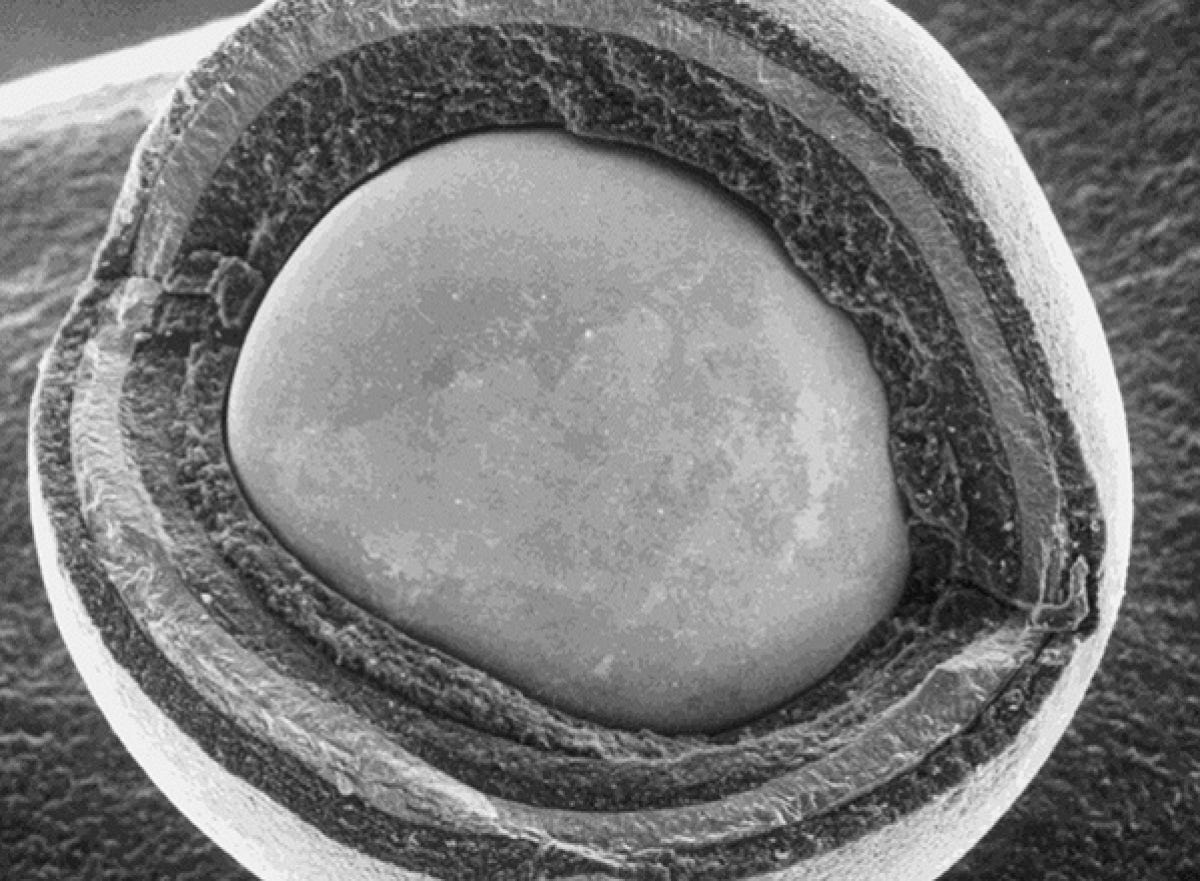

Better known as TRISO, it’s a form of reactor fuel where uranium kernels are encased in three layers of ceramic coating design to absorb the nasty byproducts that form during the atom-splitting process. You know, the stuff that ends up as radioactive waste. In theory, these poppyseed-sized pellets could have replaced the giant concrete containment vessels that cordon off reactors from the outside world. But, despite being invented in the 1960s, TRISO never took off.

Now, however, it’s having a moment as reactor developers seek to commercialize high-temperature gas-cooled reactors. Since TRISO can safely reach higher temperatures than traditional fuel without melting down, it’s the fuel of choice for companies that want gas-cooled reactors to replace fossil fuels in industrial applications such as chemical processing.

In Heatmap this morning, I had a scoop on a deal between the fuel giant BWX Technologies and Antares, a rather unusual microreactor startup, to ramp up production of TRISO.

Here, I explain what makes Antares stand out:

X-energy, the nuclear startup backed by Amazon that plans to cool its 80-megawatt microreactors with helium, is building out a production line to produce its own TRISO fuel in hopes of generating both electricity for data centers and heat as hot as 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit for Dow Chemical’s petrochemical facilities. Kairos Power, the Google-backed rival with the country’s only deal to sell power from a fourth-generation nuclear technology — reactors designed to use coolants other than water — to a utility, is procuring TRISO for its molten fluoride salt-cooled microreactors, which are expected to generate 75 megawatts of electricity and reach temperatures above 1,200 degrees.

Then there’s Antares Nuclear. The California-based startup is designing 1-megawatt reactors cooled through sodium pipes that conduct heat away from the atom-splitting core.

…

Unlike X-energy or Kairos, Antares isn’t looking to sell electricity to utilities and server farms. Instead, the customers the company has in mind are the types for whom the price of fuel is secondary to how well it functions under extraordinary conditions.

“We’re putting nuclear power in space,” Jordan Bramble, Antares’ chief executive, told me from his office outside Los Angeles.

Just last month, NASA and the Department of Energy announced plans to develop a nuclear power plant on the moon by the end of the decade. The U.S. military, meanwhile, is seeking microreactors that can free remote bases and outposts from the tricky, expensive task of maintaining fossil fuel supply chains. Antares wants to compete for contracts with both agencies.

“It’s a market where cost matters, but cost is not the north star,” Bramble said.

Unlike utilities, he said, “you’re not thinking of cost solely in terms of fuel cycle, but you’re thinking of cost holistically at the system level.” In other words, TRISO may never come as cheap as traditional fuel, but something that operates safely and reliably in extreme conditions ends up paying for itself over time with spacecrafts and missile-defense systems that work as planned and don’t require replacement.

But there are some real critiques of the U.S. strategy for TRISO.

To start, experts told me it’s better suited for large-scale high-temperature gas-cooled reactors (something with about 600 megawatts of electricity output) than microreactors that pump out double-digits of power.

China, which operates the world’s only commercial high-temperature gas-cooled reactor at the moment, also generates its own TRISO fuel.

Beijing’s plans for a second reactor based on that fourth-generation design could indicate a problem for the U.S. market: TRISO may work better in larger reactors, and America is only going for micro-scale units.

The world-leading high-temperature gas reactor China debuted in December 2023 maxes out at 210 megawatts of electricity. But the second high-temperature gas reactor under development is more than three times as powerful, with a capacity of 660 megawatts. At that size, the ultra-high temperatures a gas reactor can reach mean it takes longer for the coolant — such as the helium used at Fort St. Vrain — to remove heat. As a result, “you need this robust fuel form that releases very little radioactivity during normal operation and in accident conditions,” Koroush Shirvan, a researcher who studies advanced nuclear technologies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told me.

But microreactors cool down faster because there’s less fuel undergoing fission in the core. “Once you get below a certain power level,” Shrivan said, “why would you have [TRISO]?”

Given the military and space applications Antares is targeting, however, where the added safety and functionality of TRISO merits the higher cost associated with using it, the company has a better use case than some of its rivals, Shrivan added.

There are alternative formulations that could make TRISO more effective for Antares’ reactors, but they’re not well studied.

David Petti, a former federal researcher who is one of the leading U.S. experts on TRISO, told me that when the government was testing TRISO for demonstration reactors, the price was at least double that of traditional reactor fuel. “That’s probably the best you could do,” he said in reference to the cost differential.

There are other uranium blends inside the TRISO pellets that could prove more efficient. The Chinese, for example, use uranium dioxide, essentially just an encased version of traditional reactor fuel. The U.S., by contrast, uses uranium oxycarbide, which allows for increased temperatures and higher burnups of the enriched fuel. Another option, which Bramble said he envisions Antares using in the future, would be uranium nitride, which has a greater density of fuel and could therefore last longer in smaller reactors used in space.

“But it’s not as tested in a TRISO system,” Petti said, noting that the federal research program that bolstered the TRISO efforts going on now started in 2002. “Until I see a good test that it’s good, the time and effort it takes to qualify is complicated.”

Anyway, there are plenty of other details in the full piece, which you can read here.

Support independent energy reporting. Sign up for a premium subscription today:

Signing off from sunny Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where the some scumbag from Staten Island attacked a 12-year-old girl for wearing a hijab. Thankfully, the person is being charged with a hate crime.